Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in

–Leonard Cohen, Anthem

It begins here, in a reminiscence of where we were a year ago. Looking for something to read I picked an old book from the shelf and dusted it off. It was a copy of the Vimilikirti Nirdesa Sutra, “Pure Land,” (Shambala Press, 1975). There was a photo, I must have used it for a bookmark.

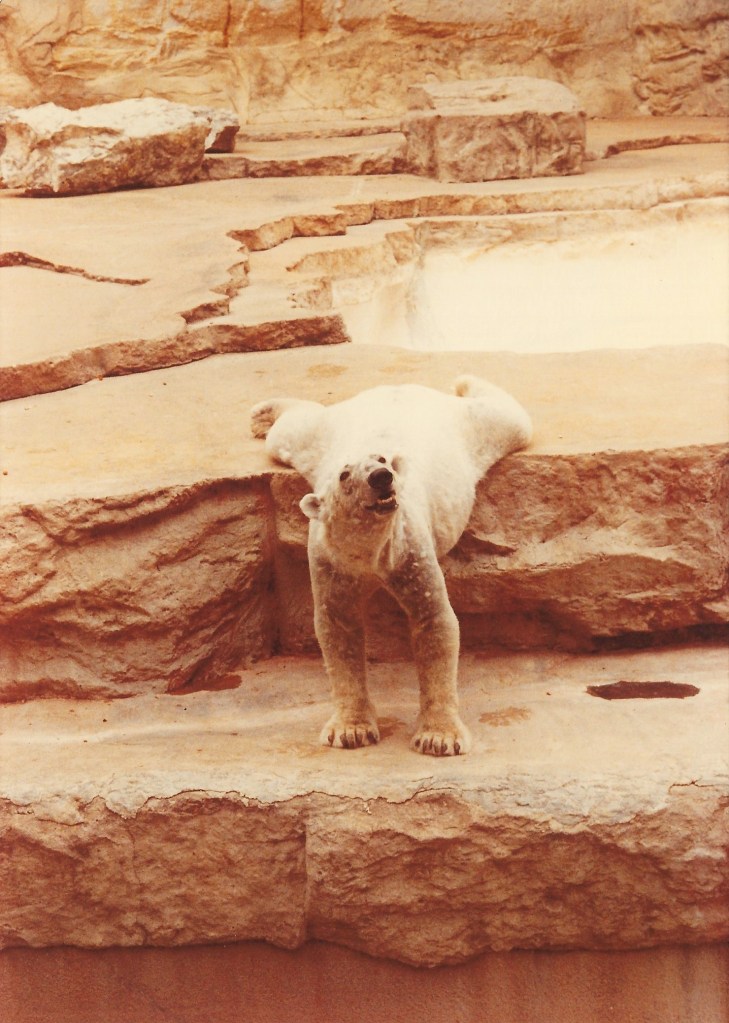

It was taken in the summer of 1978 at the San Antonio Zoo. A polar bear, in all that Texas heat, waiting to have her swimming pool refilled. A Polar Bear, living in captivity in Texas, surely there is something awry, out of balance, just by the existence of this predicament.

A year or two later there was the film by Godfrey Reggio and John Cage, whose title was a Hopi word for this condition: koyaanisqatsi, life out of balance. I think I have felt it since childhood. This is nothing special. I think we are all experiencing this, one way or another.

On the back of the photo were scribbled the important words, “Dvorak: Violin Concerto in A minor, opus 11.” Nowadays music is instantly available, and one can find the recordings anywhere. I am a fan of Apple Music–and mirabile dictu, there it is: played by Isaac Stern . Back then, one had to shop for vinyl or try to tape the music from an FM broadcast, hit or miss, or wait for Isaac Stern to show up, as he did with the San Antonio Symphony, many times, for many years. Nothing out of balance there! The KMFA program guide came monthly by regular mail. FM radio was still a posh, comparatively new thing. Heard it on the radio. Wrote the title on any scrap of paper.

I still have taped cassette recordings of Sunday evening Boston Symphony concerts, even though I no longer have a tape player. And lately, I have found other lists, as I sift and discard what I can. I even found one on my iPhone:

Delius Summer Night on the River

Copland Quiet City

Teleman Sonata in E minor (septet)

All works that must have affected me some way or another. Uncover, discover, discard.

Procrastination! I had to have heard the music, and been motivated to scribble something on a scrap of paper. But this story, which looks static, is actually moving too fast, can never be completed. A teaspoon at a time, done, with a little effort, we’re already leaving 2020.

Pure Land teaches Śūnyatā, which might be called a state of being, or a meditative state, or an aspect of reality based in that state. It explains the nondual, which can be experienced, and puts forth the suggestion that much of reality is illusory. But there is this purpose, an end to suffering among living beings; a purpose of mitigating ignorance, that is cause for moving on. What is the right course of action, given this condition of koyaanisqatsi so evident in present-day global crises, that has begun to present an ontological threat to life itself?

I don’t claim to be an expert about any of this. The above was lifted from Wikipedia, heard somewhere, or has to do with something I remember having seen or read about somewhere.

Meanwhile, back on Planet Earth, the warming, scarcity of freshwater, the global threat to biological diversity and perhaps life itself all evoke within me a profound sadness, mixed with a hope that this the early anthropocene era is not also the late.

For the past 70 years and until recently, the worst threat to humanity was considered to be nuclear arms proliferation. The Doomsday Clock printed on the front cover of each issue of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists has presented that assessment since 1947. In 2007 the editors added climate change to their list. In 2012 the clock read five minutes before midnight. It was two minutes before when I first began attempting to write this, late in 2019. A couple of weeks ago, something like 90 seconds. I have not checked since. The annual report does not mention the novel coronavirus pandemic; and although not included in the threat assessment, the report does mention disruptive technologies as an as yet unassessed threat.

The COVID-19 pandemic is clearly cause enough to stop and consider the future of life, as a tsunami of change in social and economic organization is underway. Again, these scribblings, originally inspired by experiences at Santa Fe in 2019, cannot keep up with the story. Home is an isolated station connected to the rest of the world through the miracle of modern media and telecommunication. The Jetta has been repurposed as the Terrestrial Excursion Module (TEM), and there are antiviral protocols observed before entering or leaving the TEM.

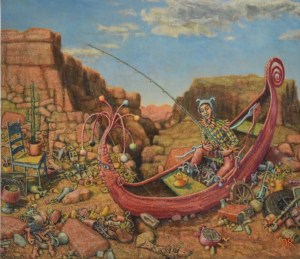

One does not have to look far to find these sentiments in art. Last summer, at the Santa Fe art market, I went looking. In a Forest Glade presents obliviousness to–well, oblivion, a degraded dystopia, and that clock, ominously dangling from a fishhook, not in some future, but already present. What is seen? esse est perspicere, reality an aspect of the ego.

As an antidote to this dismal idea, I hope to show that a discussion of what is possible, at the least exploring best approaches, and stay unstuck from the paralytic effect of the cortisol-response-inducing barrage of social media, hypnotic television, and other solipsistic junk piling up around us.

It is time to consider real-world solutions, ideas and projects already underway, at this moment of reflection as to what to do next. Of course, this brings up–what else? Another list.

“Unless humanity learns a great deal more about global biodiversity and moves quickly to protect it, we will soon lose most of the species composing life on Earth.” – E.O. Wilson

The making of past due reparations owed the planet presents a moment of an opening of human potential, and a counterpoint to the alienation and continual distraction of the present day. There is a practical purpose to this–well, practice. It is meeting the world on all fronts, without judgement and with a purpose of restoration and healing, and a remembrance, as well as a vision of the future, that can guide that work of saving saving what is left of the planet itself.

There is no advocacy here of a sort of environmental Ghost Shirt Society. Instead, what is needed is to take a hard look at what is the case, and find there ideas as to what to do next.

There was a moment of inspiration in a wonderful interview at San Diego, Jack Dangermond with E O Wilson and Jane Goodall. I cannot recommend the video enough.

One takeaway is Jane Goodall’s observation that the restoration has to be formed by local initiatives that in the aggregate will have a global effect. This is not to deny a need for national and global environmental laws and policies, but there is no substitute for local knowledge and experience, in this instance restoring overworked and eroded lands east of the Gombe Preserve, where Goodall had worked in the1960s and 70s. Invert the conventional wisdom, she says, that one should “think globally and act locally.” This is a perfect strategy for paralysis as no one has a global overview. Instead, the bumper sticker should read the obverse, “think locally, act globally.”

E O Wilson discusses the feasibility of setting aside half the planet as a wildlife preserve. We know the solution to dependency on fossil fuels is no longer a technical but a political problem. We have the technology and a capacity for sustaining the human population of the planet, while protecting most of is biological diversity. An empirical formula, derived from a century of data gives a relationship between the area of a preserve and the percent of species it protects. By that reckoning, setting aside 50% of the terrestrial (non-marine) land of the planet could still protect 88% of its species. This project, setting aside half the land as a wildlife refuge, would be humanity’s greatest achievement. For now, the highest priority is the ongoing performance of a biological survey of the planet. Let’s do this.

[an update, October 17, 2020 a peer-reviewed survey is presented in Nature, Global Priority Areas for Ecological Restoration submitted in August of 2019 and accepted for publication Sept. 8, 2020]

So, a couple of weeks after the ESRI conference in July of 2019, I almost accidentally attended a talk by Dekila Chungyalpa, at the Upaya Zen Center at Santa Fe, “Restoring resilience in Nature, Community, and Ourselves.” Dekila is a fellow at the Yale School of Forestry and currently directs the Loka Initiative at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“We should remember that the earth loves us, we are her children.” There is significant work underway by local organizations and NGOs, environmental and developmental initiatives afoot in the Sub-Himalayan countries are, or soon will be, needed here in Rural America as well.

“This work has included coordinating over 50 monasteries and nunneries in the Himalayas, which are carrying out reforestation, climate preparedness, disaster management, and freshwater conservation projects.”

In a footnote from Chapter Three of the Vimilakirti Sutra, Charles Luk comments that “perfect salvation in Nirvana is useless if a Boddhisattva neglects his work of salvation.” This is in response to Sāriputra’s excusing himself from Buddha’s request that he “Go to Vimilakirti and enquire after his health on my behalf.” Sāriputra is too confounded by Vimilakirti’s previous remarks, that meditation is not necessarily just sitting, but nonappearance of the body, of “giving no thought to inactivity when in nirvāna wile appearing in the world with respect-inspiring deportment; not straying from the truth while attending to worldly affairs…” So, Sāriputra, and several others, do not consider themselves qualified to enquire after Vimilakirti’s “health.” We had had an early indication that Sāriputra is ready for a realization but not yet enlightened, as when the Goddess dropped flower petals on the congregation, he must have been one of those to whom the petals stuck–the petals did not stuck to the already enlightened. And one by one, emissaries decline to being sent to make an enquiry, each having returned from the experience by a newly-discovered road.

The story is not difficult, or a dense classical work, it is brilliant light opera. Vimilakirti is hardly a monkish iconoclast. He is worldly, and usually a hale fellow well-met, who participates in all levels of reality from the market place to the miraculous. At one point we see his humble suburban house transformed into a vast cathedral at the scale, say, of the solar system, with seating for 32,000, and so on; all of it mundane but transcendent experience that at bottom conveys an awareness of the sanctity of all that exists.

The first chapters of the Pure Land Sutra present a sea of miracles, all around us and every day, but the story, and what follows, seems to begin here: “Please call on Vimilakirti on my behalf and enquire as to his health.”

–to be continued

I realize that I’m beginning to sound more like a marine recruiter than a biologist. But you know, we are entering an era when a radically new view of nature, of the natural world, is not only inevitable by the advances in science and the concern people have about their personal environment, but also by the amazing things awaiting discovery. As we begin to work through these millions of species that remain unexplored, and I would like to see a society in which to do this kind of exploration, to find out something about every one of these species, large and small, that allows them to maintain their existence, that has allowed it, for millions of years, enough so that they can live for millions of years into the future, and in so doing, gain a mastery of our own environment. After all, we live in a living environment. We don’t live on the moon. We’re not ready to go to Mars. We live on what may be, and I think almost certainly is, the only life-bearing planet in the solar system.”

“If we can’t save them, we can’t save anything.” – E.O. Wilson

(from the ESRI user conference at San Diego, July, 2019)